Chemistry's open access dilemma

Chemistry's open access dilemma

It was no surprise when, on 13 November, President Bush vetoed a bill that aimed to make all National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded research publications freely available on the web. After all, the 'open access' policy was just a tiny part of a $150 billion multi-agency proposition which Bush had lambasted as 'a spending spree'.

Few chemists publish in open assess journals

But the saga has highlighted a widening rift in the chemical community over open access publishing - and the contentious provision could yet be revived.

The bill, passed by Congress earlier in the month, would have forced over 200,000 researchers worldwide, including many chemists, to post all peer reviewed findings on PubMed Central (PMC) within 12 months of publication in a traditional journal.

The agency's current policy of simply asking grantees to deposit their articles on PMC has resulted in only 4 per cent actually doing so.

Major scholarly societies joined the Association of American Publishers (AAP) in lobbying against the proposal, including the American Chemical Society (ACS), the American Association for Clinical Chemistry, the Biochemical Society, and the RSC (publishers of Chemistry World).

Nonetheless, with a majority of 274-141 in the House of Representatives backing the bill on 8 November, the proposal may yet make its way into law, even if that has to wait for the next administration.

But the battle lines are already being drawn. The ACS wants the NIH policy to remain voluntary. 'Depending on how they implement this, it could represent a federal taking of copyrighted materials,' ACS spokesman Glenn Ruskin told Chemistry World.

A compulsory policy would need costly monitoring and penalisation systems, Ruskin said. 'Why expend monies on a mandatory policy, when they could get to their endpoint a lot quicker if they just worked more cooperatively with the publishers?'

'The idea of public access to research information is a little bit specious,' added Robert Parker, managing director of RSC publishing. 'The UK government will be funding the London Olympics in 2012, but that doesn't mean that everybody can have free tickets - there is a big difference between funding something and having it be freely available.'

But the open access provision is endorsed by a coalition of more than 200 academic libraries, the US Chamber of Commerce, and numerous scholarly societies.

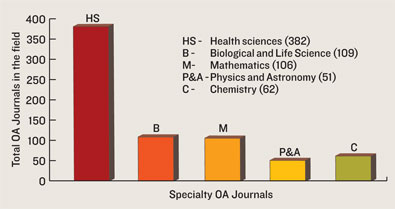

Titles listed in the Directory of Open Access Journals, sorted by discipline

They're concerned that the academies are acting more like profit-hungry companies than scholarly associations. And in October, an anonymous memo from an alleged 'ACS insider' ratcheted up the tension by accusing the society of working to undermine the open access movement. Circulated to librarians, university administrators, and to at least one public listserv, it claims that 'management is much more concerned with getting bonuses and growing their salaries rather than doing what is best for membership.'

The ACS argues that staff bonuses are tied to the financial performance of the entire organisation. 'If we weren't financially viable, that would position us poorly to advance our members' needs,' Ruskin said.

Counterstrike

Meanwhile, a campaign launched a few months ago by the AAP to communicate the risks of government interference in scientific and scholarly publishing is becoming increasingly controversial.

The Partnership for Research Integrity in Science and Medicine (PRISM) argues that the Congress bill could damage peer review by compromising the viability of non-profit and commercial journals. Predictably, the campaign has sparked outrage among open access lobby groups. In the wake of the furore, nine publishers have disavowed PRISM, including Cambridge University Press, Oxford University Press, Columbia University Press and University of Chicago Press. The ACS - which had been closely involved with PRISM - has now also played down links with the campaign.

Wider impact

If it is ever signed into law, the new NIH policy could filter down to other US federal agencies and affect disciplines beyond the biomedical sciences.

For the moment, that looks unlikely. Bush vetoed the bill because, in his words, legislators were 'acting like a teenager with a new credit card', and not specifically because of the open access provision.

However, the White House has also recently warned that any open access policy should consider 'the possible impact that grant conditions could have on scientific research publishing, scientific peer review and on the United States' longstanding leadership in upholding strong standards of protection for intellectual property'.

Meanwhile, in the UK, progress on the issue has ground to a halt. Nearly four years ago, the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee launched an inquiry into the scientific publishing industry.

The committee's July 2004 recommendations, which included a proposal to make all publicly funded scientific research in the UK freely available online, were ultimately rejected by the government.

But the drumbeat for open access publishing has been growing louder over the last decade.

PubMed Central now contains over one million items, such as articles and editorials, and is said to be growing by at least 7 per cent annually (although similar growth is seen across conventional journals, too).

And physicists have arXiv - which houses preprint articles dating back to 1991 and has more recently been expanded to include disciplines like mathematics and computer science. The database contains over 440,000 e-prints with around 4000 added every month.

Chemical equilibrium?

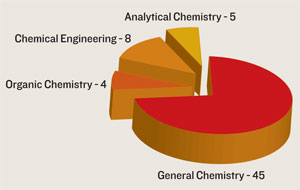

Chemistry, however, has yet to embrace either open access or pre-print archives (see 'Surfing Web2O', p46) . While there are more than 60 small open access chemistry journals (see figure), no major chemistry publications are fully open access.

According to Bryan Vickery, editorial director of Chemistry Central - an offshoot of open access publisher BioMed Central - the most important resources for chemists, like Chemical Abstracts and the Beilstein Database, are still locked behind hefty subscription fees.

'Many of the problems we are helping to solve are biology-related,' he said. 'We need to be maximising the visibility of our outstanding research, not hiding it behind subscription barriers.'

The fields that have more readily welcomed open access are those with a pressing need for widespread collaboration. For example, high energy physics traditionally has a very strong preprint culture, partly because researchers must cooperate to efficiently use the incredibly expensive technology they need.

Many chemists, on the other hand, are not eager to share their data before publication because their experiments could be repeated quickly and easily in another lab. In addition, unlike particle physics, significant areas of chemistry lend themselves to patentability and commercial exploitation.

Open access chemistry journals (Directory of Open Access Journals)

Brave new world

As a result, the steps taken by the RSC and ACS to enter this new world of publishing have received a stilted response from chemists.

For roughly a year, the RSC has had an Open Science service that allows authors to pay to make their article freely accessible to all. The basic fee for a primary research article is £1600 with a 15 per cent discount for RSC members, owner societies of RSC journals, and authors from subscribing organisations. So far, just four authors have participated.

Likewise, only 40 articles are available through AuthorChoice, the ACS's one-year-old foray into open access, which has an upfront fee of $3000 for non-ACS members with discounted rates for members and subscribing institutions.

'Most practising chemists in the first world have reasonable if not excellent access to the journals they need or want,' explained Steven Bachrach, a computational chemist at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas, US.

'OA just does not really offer much advantage for these people - and a serious disadvantage because now they have to pay to publish - and where is that money going to come from? Not from their grants.'

However, Vickery believes that a growing number of members of not-for-profit learned societies are questioning whether the large surplusses they earn from their journals are being wisely spent - a point roundly refuted by the societies in question.

And some chemists now see the rise of open access as inevitable. 'Daily we see more people coming onboard . any company or publisher who fails to prepare for open access is being very foolish,' said Peter Murray Rust, a chemist who leads a research team at the University of Cambridge, UK, and is an ardent open access advocate.

Indeed, there are calls for bold and decisive leadership on this increasingly divisive issue from all sides of the chemistry community. 'Vision is needed. Where we are at the moment is unacceptable,' said the ACS's Ruskin.

Rebecca Trager, US correspondent for Research Day USA

Opinions expressed in this article do not represent the views of the RSC, unless explicitly stated. To read the RSC policy on open access publishing vist website.

Also of interest

1 comment:

On Not Conflating Green OA with Gold OA

Nor Unrefereed Preprints with Refereed Postprints

Good summary, but it conflates the two forms of OA: Gold OA (OA publishing) and Green OA (author self-archiving of articles published in non-OA journals, in institutional (or central) OA repositories). Also conflates preprint and postprint self-archiving. All the OA mandates are Green OA self-archiving mandates, and they pertain to the published postprint, not the preprint.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Post a Comment